A Review on Innateness and Emergentism

Published:

This is the final essay I delivered for the COGS504 Natural and Artificial Minds course I took during the Fall 2018 semester. It was the first course I took from the Cognitive Science department and I enjoyed it immensely, thanks to our instructor Ceyhan Temürcü. I wanted to share it because it is the first piece of writing I prepared in the topics I aim to work on, and I really did work hard on it at the time. Aside minor fixes, I share it exactly as it is content-wise.

Abstract

In this article I give a review of the article by Bates, Elman, Johnson, Karmiloff-Smith, and Parisi (1998) on innateness and emergentism. I will start by explaining the two points of view and clarifying what the two sides defend. Then I proceed with explaining the writers’ stance on the briefly matter. In the following two sections I will elaborate on two main points I oppose in the article. While giving my claims about these points my goal is not to attack emergentism but to defend innateness and stand for more research to be done without discarding nativist ideas. I conclude by criticizing my own review and how it could be improved, and by claiming that the debate can only be ended with further neuroscientific experimental data and models.

1. Innateness vs. Emergentism

The discussions on whether certain behaviours and capabilities are innate or emergent go way back in philosophy. In his article about the controversies around innateness, Samet takes the matters back to the conflict of ideas between Empedocles and Anaxagoras (2008). His interpretation of Empedocles’ point is that the philosopher thinks the “mind is made for the world.” It is made to make sense of it from the beginning, without any external input or effect. However, on the Anaxagoras’ side, for the mind to grasp the outer world, the world must affect the mind, “shape our unformed minds into its form.”

I believe these two points summarize well the opposition. Claims about innateness, of any specific or general capability or behaviour, defend that such properties are genetically built into our being, that they are not results from any other external agents but our individual/special features. On the other side, an emergentist claim defends that such properties are not - even cannot be - stemming from our pure genetic structure. Those cognitive abilities or the knowledge one has is later put on the initially empty tabula rasa, as later called in 17th-century Empiricism (Samet, 2008).

A possible mistake that can be made here is claiming this and that capability or knowledge is purely innate or emergent. As mentioned in Bates, Elman, Johnson, Karmiloff-Smith, and Parisi (1998), it is well established that genetics and environmental agents interact in forming the complex cognitive structures of each individual. What causes the debate to persist is that we lack a testable theory explaining this interaction’s mechanisms. As Laurence and Margolis (2001) say, the difference between these two claims lies in the quantity and quality of what they see as innate. On empiricist accounts, the innate properties of the human mind are domain-neutral, simple, and few in numbers as opposed to nativist claims that these properties contain meaningful knowledge and biases about the task.

2. Views Presented in The Article

The article in question is mainly a consideration of innateness from different perspectives. The writer’s main goal is to clarify the distinction between several different concepts that are confused with innateness: domain specificity, species specificity, localization, and learnability. While doing so, they lay out several useful definitions, classifications, and criteria, which I find too detailed to fit into a summary of their ideas. In the end, they conclude that even if a cognitive capability (1) is extremely distinctive, (2) is only seen in (all normal) humans and no other species, (3) it is localized in certain parts of the nervous system and (4) it is acquiring mechanisms are peculiar or unknown to us; that cognitive capability does not have to develop from innate structures.

Bates et al. state that an upcoming emergentist explanation of development is close and state three points in support, two of which I think can be summarized by saying that the field is going more and more “public,” opening up to the insights from different fields such as neurobiology and theoretical physics. Asides from the fact that this is an excellent and inevitable course for any advanced scientific research, it could also yield results that hinder their claim. Another support for their belief is that neural networks with nonlinear dynamics produce results that explain the “emergence of complex solutions from simpler inputs” (Bates et al., 1998). Although I find their claim here solid, especially considering the possible advancements in that account during the twenty years after that article, I find it questionable to what extent these coded structures can be held as equals with human brains because, as seen in Section 3.1, the nervous network humans possess is yet to be explained in sufficient detail.

Now that I have made an overview of the debate in general and the views of Bates et al., I may proceed with my criticism of the article. Bates et al. claim that “strong nativist claims about language, physics or social reasoning have to assume representational nativism” (1998) because innate architectures and variations in timing do not possess the coding power needed to store that knowledge. After affirming that the structures housing the innate knowledge must be the brain’s microcircuitry, they claim that this representational nativism cannot reside within genetic information; so, they claim that innateness of knowledge is not a plausible scenario. What I oppose in that line of argumentation is that the architecturally innate properties of the brain circuitry may be powerful enough to encode such knowledge. The article quickly proposes that these properties are not computationally powerful enough to encode innate knowledge such as grammar. In Section 3, I will show an example from a field of neuroscientific research, namely connectomics, to show that we have little knowledge about the exact architecture of the microcircuitry of the brain and that the situation may not be so different for the neural nets or machine learning algorithms we code by hand.

On the other hand, I believe that computer scientific support can be made to bolster the case for an innate structure, namely Universal Grammar, behind language acquisition. Similarities to the transfer learning concept in computer science will be drawn to argue that such an innate structure’s existence is plausible and that its benefits match with the statements of Universal Grammar and Poverty of Stimulus concepts in Section 4.

3. A Defence of Architectural Capabilities of Cognitive Systems1

3.1. Human Nervous System and Connectomics

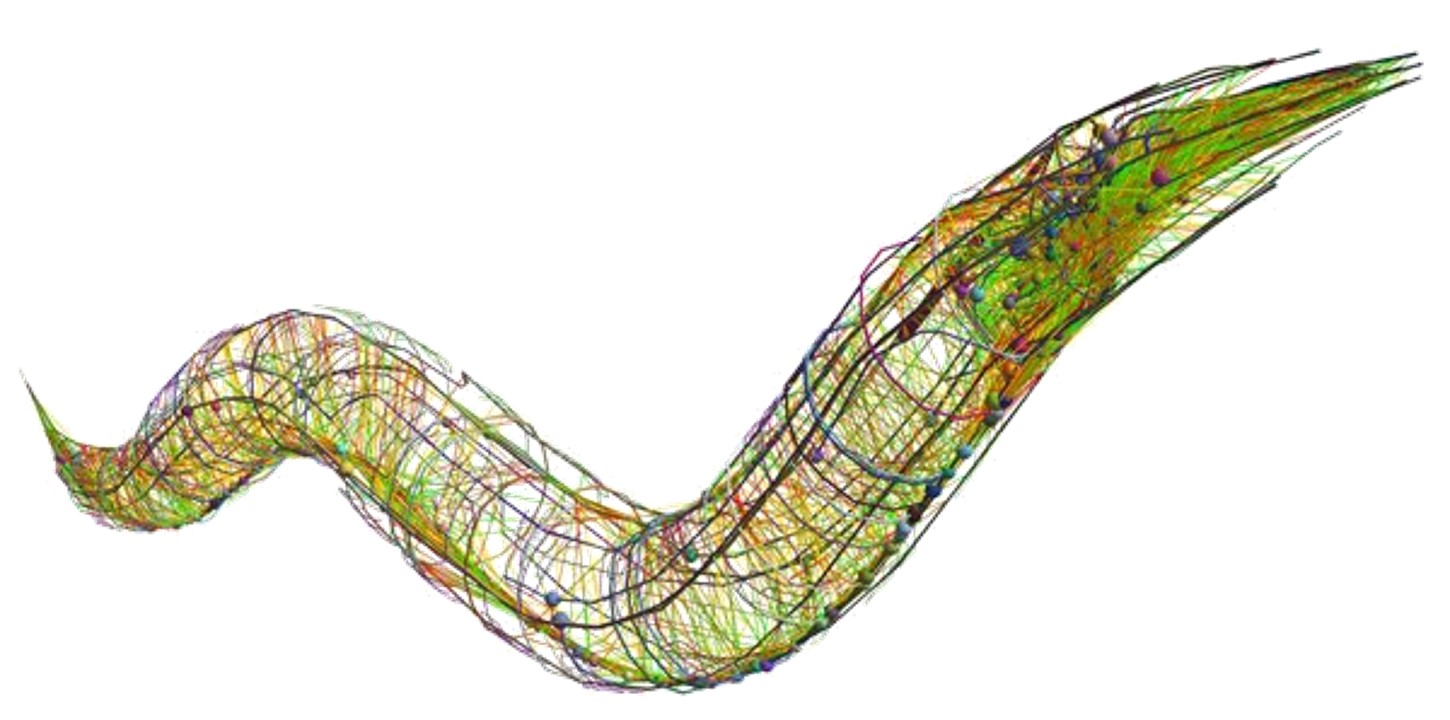

Figure 1. A 3D reconstruction of a C. Elegans worm’s connectome, fitted within its approximate body shape. Retrieved from Jabr (2012).

By Sporns, Tononi, and Kötter, a connectome is defined as the dataset describing these individual elements and their connections2 (2005). The term is not limited to humans as well: Connectomes of other living creatures have been studied as well, such as the roundworm as seen in Figure 1 (Jabr, 2012). In a broader sense, this connectome dataset represents the neural net we possess within our brains, along with its fundamental and architectural properties.

At this point in my argument, I find it necessary to revisit some definitions made in the article in question. Bates et al. define architectural constraints as the constraints or properties coming from the structuring of the elements. Then, they consider these constraints in three categories: Basic computational elements, local architecture, and finally up to global architecture, where the first comprises of a single computational element and the latter two describe the behaviour of a bigger and bigger collection of these units. Knowing that connectomics may provide us with empirical data on how our nervous system is wired, we may perhaps consult it to determine these constraints and judge their computational power.

While we may hope to consult connectomics for an answer, that is as far as we can go for several reasons: Firstly, it turns out that mapping the human connectome on a single-neuron basis is extremely difficult. Sporns et al. propose that it is not feasible and will remain so for some time (2005). The problem’s scale fits into perspective - or rather does not - when we consider the size of the dataset regarding the human connectome. Human Connectome Project offered this dataset on their website for the scientific community under the name of “Connectome in a Box,” which comprised of “eighty-seven terabytes for 1100+ subjects” (Order Connectome in a Box, n.d.). Scientists put forward projects like Eyewire to employ people worldwide in gamified neuroscience research to map individual neurons, starting from the retinal cortex (About Eyewire, A Game to Map the Brain, 2018). It is a good start, in my opinion, employing every single possible volunteer around the world in an entertaining setup for the good of neuroscience. However, evidently, there is still a way to go until we base clear-cut arguments regarding the individual neurons on such data.

It is important to note that I am not talking about the strength or quality of the connections between the neurons, which falls under the definition of representational constraints made by Bates et al. (1998), but the structures’ overall properties formed by the neurons. As understood from (Sporns et al., 2005), we do not have a quantitative measure of the connections of the neurons as well, at least on the collective level of forming neuronal nets and mapping them out explicitly, but the main point is that we do not know the architectural properties of these nets.

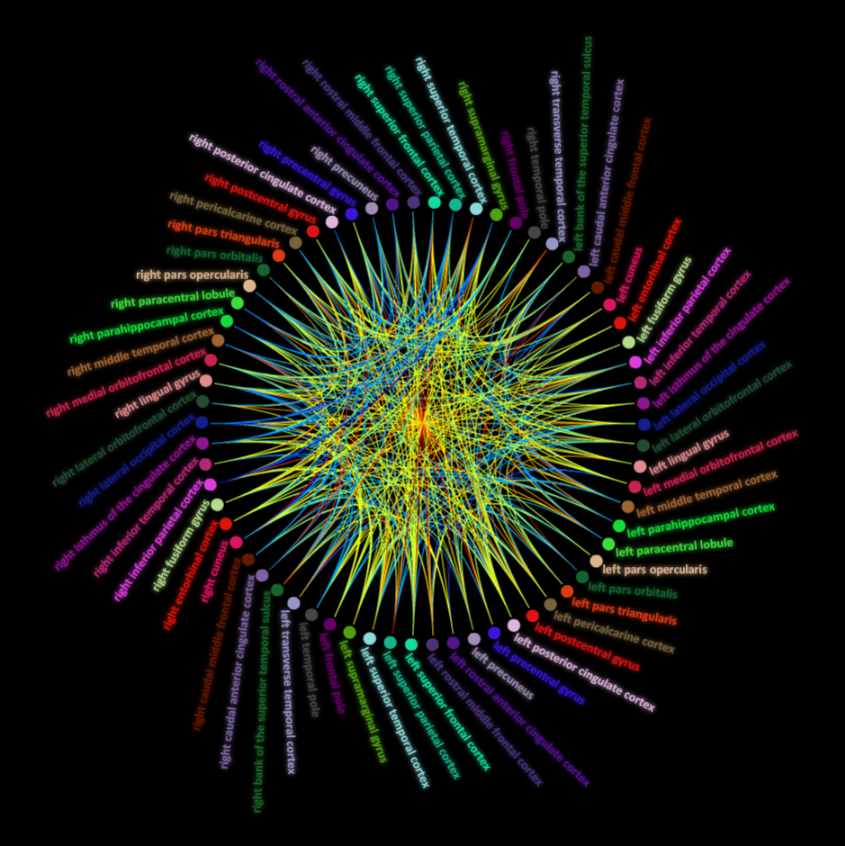

Figure 2. A visual map showing the relations between regions of the human brain and their strengths, where a warmer colour means a stronger connection. Retrieved from Relationship Viewer (n.d.).

What about the local or global architectural constraints, then? Sporns et al. confirm that this is the more achievable goal for compiling a human connectome. Figure 2 shows a visual interpretation of such data, taken from Relationship Viewer (n.d.). Nevertheless, the problem with this approach is, they say, that there is no one common way of discretizing the densely populated human brain (2005). Prinz (2006) gives several examples in the named but locationally unfixed regions of the brain. As a consequence of this indeterminacy, I do not think it is possible to talk about an evaluation of the coding power of the local -hence global architecture of the brain. I believe an indeterminacy in location also implies indeterminacy in internal structure, hence in the complete and functional description of its behaviour.

Let me now return to the article and consider the authors’ argumentation against the architectural innateness of Universal Grammar (which is further explored in Section 4) and reconsider the argumentation. Bates et al. (1998) claim that innate architectures -and also chronotopic constraints, but that is beside the point here- cannot serve as a basis to an innate Universal Grammar because:

(a) They do not have the necessary coding power for such knowledge. We have seen above that we are unable to form a map of the human brain based on individual neurons and that although we know certain regions of the brain are performing specific functions, we do not know the exact boundaries hence features of such regions. On account of these conclusions, I claim that the information we have about the human brain’s architectural structure is not sufficient to make a clear-cut judgment about the said structures because evidently, we cannot fully describe such structures, qualitatively and quantitatively.

(b) The behaviour in growth is common across species. My opposition to this argument follows from the one I did for the previous one: Our understanding of neural growth is on the individual level. The structures they form collectively are unknown to us, so although such individual behaviour is common across species, we cannot know that the maps they form do not contain any knowledge innate to different species members.

3.2. Artificial Cognitive Systems

In artificial cognitive systems, things are a bit more exposed, but not so much still. Simple systems such as the neural net given by Smilkov and Carter (n.d.) on playground.tensorflow.org may be dissected to expose their representational and architectural constraints, but this is not the general case. In Harris’ podcast about the future of artificial intelligence, Russell affirms that we may not exactly know the inner processes of the artificial learning algorithms in use, calling them “essentially black boxes” (Russell & Harris, 2016). Russell also explains that in the face of a given problem, if possible, he prefers systems designed in response to the problem characteristics, so the system is assured to work as expected. From these two pieces of information, we may conclude that an artificial system’s architectural properties might contain some information about the problem towards which they are designed to solve.

Here I must clarify to prevent any misunderstanding: I do not claim that, say, a Decision Tree algorithm or a Support Vector Machine has more expertise on a particular topic than a Convolutional Neural Net does, somehow that they know more on the subject. My claim here is that these algorithms empirically showed that they perform better or worse in, say, speed and accuracy on different problem settings. Russell gives the joking example of “grad student descent,” where they try different system designs with different graduate students on the same problem, without knowing whether each system will perform well (Russell & Harris, 2016). While this does not show that the algorithms know anything innately on the subject, we may still claim their architectural structure is better fit to specific situations, so we cannot discard the idea that we may infer something about the problem itself by just looking at the structure of the best-performing algorithm.

Although it is a weaker claim than that in the previous section about the human nervous system, I claim architectural properties may still possess information. Without further investigations, especially on the human nervous system, we cannot precisely measure the effect of architectural constraints on the cognitive capabilities we have.

4. A Defence of the Innateness of Universal Grammar

In this chapter of my review, I will try to defend innateness for a specific - yet not surprisingly, extremely featured - case: That of Universal Grammar. I will first explain the concept of transfer learning in computer science and Universal Grammar with its principles and supporting arguments. Once the definitions and certain clarifications are given for both concepts, I find the claims I will defend will prove to be self-evident.

4.1. Transfer Learning and Its Benefits

Torrey and Shavlik explain transfer learning as a method of transferring information between learning algorithms (2009). The method is used to increase the efficiency of the one algorithm by “showing” it another pre-trained algorithm to serve as a starting point or as “leveraging knowledge.”

On that account, few basic definitions are essential. Source Task is the goal of a pre-trained algorithm that provides its existing knowledge. Note thatthis algorithm is pre-trained: This distinction will be significant later on. Target Task is the task that the to-be-trained algorithm will solve. It starts as a “regular” learning algorithm, needing a dataset of its own to learn. This specific dataset may or may not be included in that of the source task. So, the to-be-trained to solve the target task uses another algorithm that solves the source task, while still needing a dataset to learn.

A simple example of transfer learning is my own experience with it at IBM. My project group was given the simple task of making a small demo bot perform facial recognition. Not having the required knowledge to write a full facial recognition algorithm; instead, we decided to treat our faces as objects and implement an object recognition algorithm. IBM’s artificial intelligence system, Watson, already has a visual recognition algorithm (source task) that can classify an object into an extensive range of classes. We supplied IBM Watson with our pictures as positive example classes and random faces we found online as the negative example class (dataset). After approximately 40 pictures for each group member and a random - but sufficient - number of negative examples, the algorithm was performing well enough to recognize the faces of our group members (target task) and reject other faces.

Obviously, 40 pictures for each positive class is not nearly enough to train such an algorithm, especially given that it is not specifically a facial recognition algorithm but a visual recognition one3. This illustrates one of the key benefits of transfer learning: It drastically decreases the size of the needed dataset, so the target task performs better under small datasets. This fact is also stated by Donges (2018) in his description of transfer learning, along with another advantage: Training time. Our custom classifier trained in approximately 10 to 15 minutes. For such a complex task of facial (or object for generality) recognition, this is near to nothing. Donges states that a deep neural network may take days or even weeks to complete learning and that transfer learning is a major tool in obtaining short training time with relatively little training data.

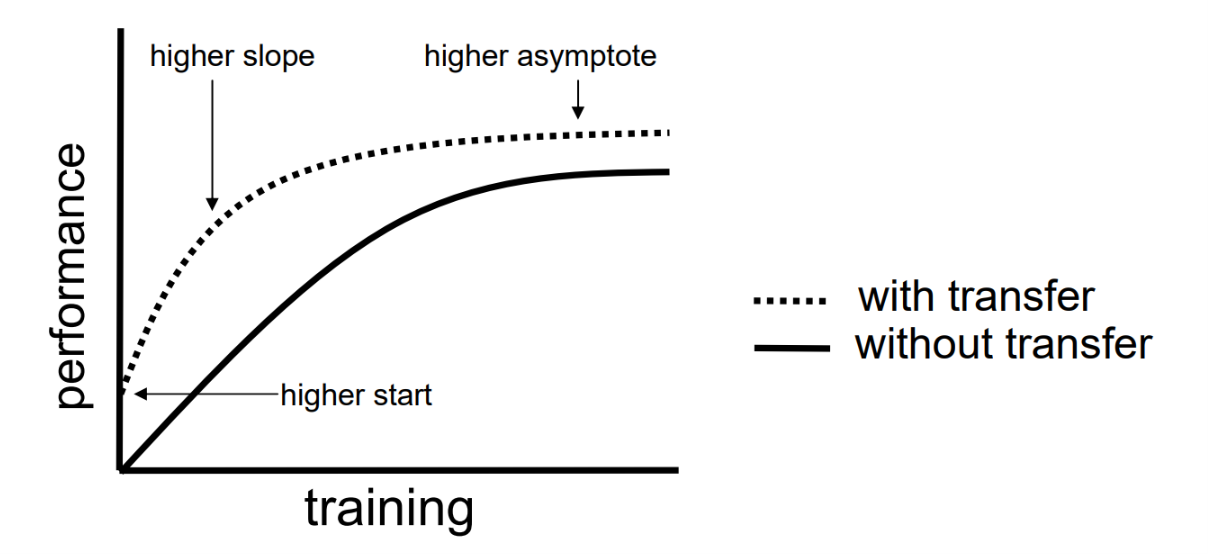

Figure 3. A plot showing the performance of a learning algorithm with and without transfer. Retrieved from Torrey and Shavlik (2009).

Figure 3 (Torrey & Shavlik, 2009) compares algorithm performance during training vs time, with and without transfer. Torrey and Shavlik show the three benefits of transfer learning on this plot: Higher start, higher slope, and higher asymptote. Each of these benefits can be explained in the following ways:

- The starting point is a measure of how close the algorithm is to understand the pattern in the training set before being exposed to it, at least to a significant portion of it. A higher start means the algorithm has “an initial understanding” of the pattern before training, making sense since it is extracting that knowledge from the source task.

- The slope is the measure of how fast the algorithm learns from the dataset. A higher slope means that the algorithm is learning faster, in particular, utilizing both the knowledge of the source task and that it extracts by itself from the dataset.

- The asymptote can be considered as the algorithm’s “ultimate intellectual capability.” A higher asymptote means that the algorithm learns more about the dataset upon learning, which matches our intuition again.

Now having a basic knowledge of transfer learning, let me summarise the Universal Grammar idea and the Poverty of Stimulus argument.

4.2. Universal Grammar (UG) and Poverty of Stimulus Argument (PoS)

As quoted by Johansson (1991), Chomsky defines Universal Grammar as “the system of principles, conditions, and rules that are elements or properties of all human languages… the essence of human language”. So, one point I understand from that definition is that nobody speaks Universal Grammar. It is not a language to be spoken, but a framework that dictates what language is or might ever be. I like to think of it as wet clay: It is not reasonable to ask the shape of wet clay or its function as a tool in your everyday life. It has not yet taken form, dried, and baked so that it may possess these properties. However, in its wet form, clay still somehow dictates what it can or cannot become. For example, we cannot make a screwdriver out of it because the dried clay is not sturdy enough for such operations even if we can shape it properly, or a rubber band because it lacks elasticity. Going back to the formalism behind Universal Grammar, Johansson (1991) gives three arguments for its case for innateness:

- All humans acquire language with minor exceptions, whereas no other animal (as far as we know) do not.

- Languages worldwide share several “language universals,” which suggests that it may be our species’ innate property.

- Without an innate grammar structure/framework, it would be very difficult or even impossible for us to acquire language.

These arguments bring me to the Poverty of Stimulus argument, which deserves attention on its own. Although it has met strong opposition, PoS is still a valid argument. Laurence and Margolis (2001) summarize the standardized version of the argument as follows:

- There are an indefinite number of possible sets of principles explaining the regularities in the primary linguistic data, and

- We have no reason to assume either of them is more complex or simpler than the others.

- Children are not exposed to the type or quantity of information that is needed to select a set of principles among others,

- Meaning that had they been empiricist learners, they would not be able to arrive at a common set of grammatical principles.

Children do come to find the correct grammatical structure.

Hence

- Children cannot be empiricist learners. My goal here is not to defend the argument, which Laurence and Margolis (2001) do thoroughly in their article. So I will not be questioning the validity of the argument and take it as a fact moving on.

4.3. Transfer Learning and Universal Grammar

In Section 4.1, I have presented the definition and advantages of transfer learning, whereas, in Section 4.2, I summarized the arguments for Universal Grammar and of Poverty of Stimulus. I find that there is a striking relationship between the two concepts. Now remember the three definitions made for transfer learning and consider matching

- the target task with language to be learned,

- the dataset with the primary linguistic data and

- the source task with Universal Grammar, although I find it more appropriate to call it as a source model in this case,

and let us see if this matches the theoretically expected benefits of transfer learning methodology.

The most apparent and robust benefit is automatically drawn between PoS and the higher start/sufficiency of small datasets. The conclusion of the PoS is that children are not empiricist learners, so they possess innate biases, which translates as innate knowledge, about the concept of language (Laurence & Margolis, 2001). Also, the key premise, in fact its eponymous premise, of the PoS argument is the fact that the primary linguistic data the children are exposed to is not sufficient for mere empirical acquisition of language. Considering these two points, they fit perfectly with the benefits of transfer learning, the former implying the higher start and the latter implying the sufficiency of smaller datasets.

This idea of UG serving as an initial, raw model for languages to be learned also fits with its definition. It is a general framework in which every single grammatical structure in every language fits, like an ultimate recognition algorithm that knows every feature of its domain. The transfer of knowledge during language acquisition is equivalent to picking a specific pattern within this parent framework. For the analogy of wet clay, the language acquisition process is analogous to taking a piece of clay, then shaping and baking it; the difference being that after baking, the clay cannot take another shape, whereas humans do acquire second languages.

An important distinction is that UG is a source model and not a source “task”: It does not serve any purpose other than providing a linguistic prior to the learner. In other words, one does not “speak” in UG, at least entirely. In transfer learning, this source algorithm must somehow acquire that knowledge from somewhere, which implies its own training process. However, UG is not -and cannot be- trained beforehand almost by its definition, so it must come as an innate structure.

A weaker but still relevant similarity can be drawn to the higher slope benefit as well. It is well known that language acquisition occurs over a critical period during development (Snow & Hoefnagel-Höhle, 1978). Considering the size of the knowledge gained at the end of this period, we could assume that the rate of learning is extremely high. What it is higher from could be the recurrent net of one of Elman, one of the writers of the main text. Garson (2018) states that Elman managed to train a neural net to complete an English sentence near perfection. However, it required him to apply intensive training, using a simple version of the English grammar and a small vocabulary of 23 words. The amount of knowledge acquired by this network is, without a doubt, minimal compared to the immensity of English grammar and vocabulary, and knowing this network required intensive training, we may assume its performance vs training curve has a smaller slope compared to the possible curve of a child acquiring knowledge. The similarity is self-evident within these intuitive assumptions, but the claim requires qualitative measurements, which are very hard to obtain.

The only relation that I think is impossible to draw between the UG claim and the benefits of transfer learning is the higher asymptote, which is due to the lack of experimentation, so I find it best to leave it untouched.

These similarities (one I find solid and the other not so much) make it evident that such an innate Universal Grammar concept agrees with our computer scientific expectations of an initially present model describing the task at hand, which is language acquisition. Returning to Bates et al. (1998), the line of argumentation done above illustrates that the existence of an innate UG is reasonable under the light of transfer learning, and thus claims about innateness still stand. Where this UG resides is still a subject of research, as shown in Section 3.

5. Conclusion

In this article, I reviewed the article by Bates et al. on innateness and emergentism. I started by explaining the two ideas and their opposition, followed by the claims presented in the main article. I opposed specifically two points in the article: Bates et al. claim that the human nervous system’s architecturally innate properties are not powerful enough to encode meaningfully large amounts of information. However, in the light of more recent neuroscientific discoveries, it is seen that we know little about the general mapping of the neurons. This lack of information makes it impossible to ascribe such incapability to the neural net we possess. On the other hand, the writers dispose of the idea of an innate Universal Grammar. The concept of transfer learning, which is computer scientific and does not rely on any empirical results on human anatomy, proves that such an innate framework is plausible and should not be discarded.

In total, although I find the article as a beneficial source for arguments against innateness in the light of once-contemporary scientific findings, I also find it as a poor one in depicting them fairly. In this case, the writers do not assume such a role in the beginning and it may be seen as pointless to hold them accountable for something they did not declare they would do, but I believe such an encyclopedic article is supposed to represent both sides equally. The writers must present both concepts with their supporting arguments, experimental results together with their counter-arguments towards one another, to guide the reader to find its voice on the matter and towards further reading.

There are many points in which the argumentation presented in this review can be improved. For example, transfer learning is not always a beneficial method -in which case it is called a negative transfer (Torrey & Shavlik, 2009)- could be explored within the scope of the discussion. On the other hand, the compatibility of an innate UG with the benefits of transfer learning needs more empirical and theoretical support than those presented here. All in all, the debate between nativist and emergentist claims remains, and I believe the discussion will remain relevant until further scientific evidence is presented, especially in the field of connectomics.

Notes

- Here (and further on) the term “cognitive system” is used very loosely, so that it may contain both artificial systems and human brains. Back up.

- I am hesitant to name the connections purely synaptic, since more levels of interactions via hormones and neurotransmitters etc. may also be present. Back up.

- Actual facial recognition algorithms are better adapted to extract and compare specific facial features, such as the distance between the two eyes. Back up.

References

About eyewire, a game to map the brain. (2018, Apr). Retrieved from https://blog.eyewire.org/about/

Bates, E., Elman, J. L., Johnson, M. H., Karmiloff-Smith, A., & Parisi, D. (1998). Innateness and emergentism. In W. Bechtel & G. Graham (Eds.), A companion to cognitive science (p. 590–601). Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

Donges, N. (2018, Apr). Transfer learning. Towards Data Science. Retrieved from https://towardsdatascience.com/transfer-learning-946518f95666

Garson, J. (2018). Connectionism. In E. N. Zalta (Ed.), The stanford encyclopedia of philosophy (Fall 2018 ed.). Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2018/entries/connectionism/.

Jabr, F. (2012, Oct). The connectome debate: Is mapping the mind of a worm worth it? Retrieved from https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/c-elegans-connectome/ Johansson, S. (1991, 01).

Laurence, S., & Margolis, E. (2001). The poverty of the stimulus argument. The British Journal for the Philosophy of Science, 52(2), 217–276.

Order connectome in a box. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://store.humanconnectome.org/data/cinab/connectome-in-a-box.php (Retrieved May 26, 2018.)

Prinz, J. J. (2006). Is the mind really modular. Contemporary debates in cognitive science, 22–36.

Relationship viewer. (n.d.). National Institute of Health. Retrieved from http://www.humanconnectomeproject.org/informatics/relationship-viewer/

Russell, S., & Harris, S. (2016, Nov). The dawn of artificial intelligence - a conversation with Stuart Russell [audio blog interview]. Sam Harris. Retrieved from https://samharris.org/podcasts/the-dawn-of-artificial-intelligence1/

Samet, J. (2008). The historical controversies surrounding innateness. In E. N. Zalta (Ed.), The stanford encyclopedia of philosophy (Fall 2008 ed.). Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2008/entries/innateness-history/.

Smilkov, D., & Carter, S. (n.d.). Tensorflow - neural network playground. Retrieved from http://playground.tensorflow.org/

Snow, C. E., & Hoefnagel-Höhle, M. (1978, Dec). The critical period for language acquisition: Evidence from second language learning. Child Development, 49(4), 1114–1128. doi: 10.2307/ 1128751

Sporns, O., Tononi, G., & K¨otter, R. (2005, 09). The human connectome: A structural description of the human brain. PLOS Computational Biology, 1(4). Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.0010042

Torrey, L., & Shavlik, J. (2009). Transfer learning. In E. Soria, J. Martin, R. Magdalena, M. Martinez, & A. Serrano (Eds.), Handbook of research on machine learning applications. IGI Global. (Retrieved from ftp://ftp.cs.wisc.edu/machine-learning/shavlik-group/torrey.handbook09.pdf)