Essays on Philosophy of Cognitive Science

Published:

These are the weekly quizzes for the COGS517 Philosophy of Cognitive Science course I took during the Fall 2022 semester. They are relatively short (2-3 A4 sheets at most), so I decided to gather them in a single post as I write them. They are in chronological order, and as the course progresses they -more or less- follow a certain progression of topics and questions. While they start off heavily philosophy of mind centric, I expect them to turn more to the philosophy of cognitive science each week.

- Is “Autonomous” Same as “Automated”?

- Turing Tests and Chinese Rooms for Other Minds

- Type 1 Theory of “Mind”

- Tug-of-Mind

- What Is It Like To Be In The Chinese Room?

- Theory Type of Computational Neuroscience

- Intentional Stance and the Computer Metaphor

- Computation with Different Inputs

- Putting the Mind into Context

- Turing Testing ChatGPT

And finally, here’s my end-of-term report, where I try to make an exposition of my perspective shift after taking the course. PS. As of January 22nd 2023, it lacks proper references, but I will add them in the near future. I felt comfortable sharing it as is since all the needed references are already present in the quizzes already.

Is “Autonomous” the Same as “Automated”? ⤒

First of all, I have to say that for all practical or everyday cases I can imagine, these two words seem to be synonymous: Both kinds of autonomy convey the meaning of a possibly complex process being performed independent of an external agent’s interference or control. For sufficiently complex tasks I imagine both entail implementing some sort of auto-correction upon error detection, modelling of the environment and planning on that model, and much more. I have to admit my reluctance in positing the existence of a representation, though. After all, the falling of water at a water flow seems to occur autonomously at face value, while I find it questionable that there is a representation there at all.1 So, I make no distinction between these two terms in terms of the existence of representation. Both may or may not have it, as far as I am concerned here.

When we probe the two words further and look for differences, however, I find that “automated” seems to suggest an “automator,” while “autonomous” implies no such agent. Following this distinction, what is automated is inevitably conceptually dependent on its automator, as it is this automator that designs the automated. The input-output relations of the automation process or the internal state transitions are determined by this external agent, who itself must be able to compute and evaluate such decisions beforehand. If the automated has (internal) representations, it is the automator who puts them there. The validity and fitness of these representations are entirely dependent on them, which relieves the automated from accounting for its performance. Even when we are talking about a (machine/reinforcement/artificial) learning agent, what it learns, the rules it finds or the representations it develops cannot go outside the boundaries or the meta-rules its designer imposes. The complexity or performance in behaviour and autonomy of the automated can be considered illusory or misplaced, because it is not really the automated that possesses such qualities, it is the automator.

Putting the “autonomous” at the other side of this distinction, however, makes describing the autonomous significantly more challenging than describing the automated. Firstly, the discussion above seems to remove any sort of designer from the picture of an autonomous. How does the autonomous come to become competent in the complex task it performs? Even the constraints or the well-definition of the input-output relation the autonomous performs can lose their concreteness without such a designer. One way out suggested by Dennett (2018) seems to be resorting to natural selection and evolution. According to him, the trial-and-error mechanisms of natural selection and sufficient time (in the order of thousands or millions of years) can yield “competence without comprehension,” or autonomy without a higher-level designer. The matter of representation is another problem for the autonomous: If it indeed has internal representations for aspects of its environment and its internal states (meaningful to us or otherwise), how can they come to “mean” what they do, without resorting to the God card or another higher-level being? In other words, autonomous seems a natural subject to the symbol grounding problem from which the automated is exempted, through the existence of its automator.

Lastly, I would like to make a brief discussion on the computer scientist’s view over these two kinds of autonomy. Taking Knuth’s definition of computer science, i.e. as the study of what can be automated2 (and I take the word “automated” here to include both kinds of autonomy), I find that the autonomous and the automated alike are subject to the computer scientist’s inquiry, although with significant distinctions. Because the automated comes equipped with its automator, the computer scientist’s empirical reliance is somewhat relieved. The validity and performance of the algorithm they develop can be contrasted the automator’s design criteria directly. However, without assuming the existence of a supernatural designer (like a God) or access to what can be their design process (like heresy), what is automated is almost inevitably a coder’s design. This makes the study of the automated by the computer science a search for simplification, refinement or improvement. On the other hand, the solitary nature of the autonomous challenges the empirical needs of the computer scientist: No designer, no access to internal state transition or even the guarantee of them and even no well-defined target problem with any description of desirable outputs to possible inputs. The computer scientist is left to their own devices in narrowing down and solidifying the scope of all of these open questions in the case of the autonomous. The tests of performance of any candidate algorithm/hypothesis must be based on the assumption that the observed inputs and outputs are sufficient in this assessment.

Notes

- I suspect this debate will lead the way to “nature computes” type of arguments, but more in a “nature represents” way. ↩

- While we talked as if this is Knuth’s definition in class, I discovered that in fact Knuth is quoting George E. Forsythe, who wrote about the central questions of computer science. See Knuth (1974, p. 323) for the quote. ↩

Post-Script Note: I only added the Knuth (1974) reference as I discovered that later.

References

Dennett, D. C. (2018). From Bacteria to Bach and Back: The Evolution of Minds. Penguin Books.

Knuth, D. E. (1974). Computer Science and its Relation to Mathematics. The American Mathematical Monthly, 81(4), 323-343.

Turing Tests and Chinese Rooms for Other Minds ⤒

Before attempting to adapt the Turing Test and the Chinese Room to meaning-bearing minds possibly other than humans’, I find it important to clarify what we take these experiments to be. This will allow me and the reader to judge the accuracy of the adaptation and whether the hypothesis tested by the original test is still tested in the adaptation, or what the new hypothesis tested is.

The Turing Test is the easier one to deal with among the two, as I find Turing (1950) makes its conditions rather explicit. A human questions a computer (program) and a human subject with the only means of communication with both of them being a textual medium. Both the computer and the human subject try to convince the questioner that they are human and the other is a computer through the answers they give to the questioner. In this summary, while the properties of the communication medium may seem irrelevant to the test, at least the delivery speed of the messages turns out to be of importance: While a computer can multiply large numbers in split seconds, an average human takes significantly longer.1 Therefore if the two are communicating with pigeon messengers, the questioner will find it impossible to judge how long each side took to perform such a calculation and will not be able to use a criterion otherwise available. In light of this observation, here are the ingredients to a Turing Test:

- Questioner, a human who performs the test by asking questions.

- Questionees, one human and one computer (program) who are tested via their answers to the Questioner’s questions.

- Communication Medium, a reliable and fast (let’s say with no delay) textual medium that is the only means of passing questions and answers between the Questioner and Questionees.

- Decision Criterion: If the Questioner cannot confidently identify the Questionees as human and computer, the computer (program) is said to have passed the Turing test.

The Chinese Room thought experiment is more elusive to pin down than the Turing Test is. As pointed out by Hofstadter and Dennett (2010), Searle glosses over important details by appealing to intuition and innocent yet strong suppositions to make his point. However, my goal here is not to discuss the validity of the thought experiment, therefore I will take it as it is given by Searle (1980) with as much fidelity as possible: A human subject $S_1$ who knows language $L_1$ is located in a room with an instruction manual in $L_1$ that contains correlational rules between language $L_1$ and language $L_2$, which the subject does not speak or understand its alphabet. To $S_1$, the letters of $L_2$ are mere squiggles. Another subject $S_2$ who speaks $L_2$ passes written questions into the room. $S_1$ then analyses the written note with the help of the manual and cooks up an answer in $L_2$ that they themselves (supposedly) do not understand. A cornerstone supposition in this setup is that the manual on its own can pass the Turing Test,2 so it can be taken as the written instructions to an artificial intelligence program; “Strong AI” in Searle’s words. Searle then proceeds with his conclusions, but this is enough for me now to list the following ingredients:

- Two languages, $L_1$ and $L_2$, that are significantly minimal overlap (e.g. in their alphabet) to prevent any “linguistic leakage” of meaning.

- Two subjects, $S_1$ inside the room and $S_2$ outside, who speak $L_1$ and $L_2$, respectively.3

- Manual that passes the Turing Test, in $L_1$ that serves to take in questions in $L_2$ and generate an appropriate answer.

- Communication Medium, a written, reliable and reasonably fast that is the only means of communication between $S_1$ and $S_2$.

What I found most interesting through the above analysis is that both require one or more language(s) that provide(s) the ground for the evaluation of the test/experiment. A failure case is equivalent to ineptitude in the use of that one language, in comprehension or production. Furthermore, a written form of that language is also required to block unwanted communication. Although the underlying assumption these imply, that is the written language can provide sufficient proof of the adept use of that language in general and hence indicate the existence of a meaning-bearing mind, is rather interesting to me. This is because not even all human languages have written forms, and to what extent the written form of a language can represent its oral form is debatable.4 More so, a hypothetical mind that does not use any language (written and oral alike) to communicate with other members is also outside the boundaries of these thought experiments. That only leaves room for dialects of Mentalese, i.e. languages that are privy to each meaning-bearing yet solitary mind. I find it dubious that such minds can even exist or are discoverable even if they do, so I do not consider that case with comfort. Therefore further on, I will assume that a meaning-bearing mind uses a language in any form (sound waves, electromagnetic waves, etc.) that can be transcribed through a fixed set of written symbols (alphabet). And with these ingredients in mind, I can attempt to adapt the thought experiments to other meaning-bearing minds.

The Turing Test then has to be adapted first since the Chinese Room depends on it, and I find it rather easy to adapt. Simply the human is replaced with the other meaning-bearing mind (bird, Martian, etc.), and the pieces work together in the same way as before. Let’s take it to be a Martian bird. Then The Martian-Bird Turing Test works as follows: A Questioner Martian Bird Martian-tweets questions that are passed to the Questionees computer and another Martian Bird. The computer and Martian Bird try to convince the Questioner that they are the true Martian Bird and the other is the computer. If the Questioner Martian Bird cannot reliably/confidently decide which is which, the computer passes the Martian Bird Turing test.

While this adaptation was rather easy, it makes no prediction on the possibility of success or failure for different species as it should, just like the original one. That is, even if we knew the Turing Test could be succeeded by a computer programmed to speak an arbitrary human language, we could not tell whether we could have a similar guarantee for another meaning-bearing mind. This implies the following scenario: Let’s say we organise a universe-wide Turing Test festival and run the Turing Test (their adaptations) with all the different kinds of meaning-bearing entities from across the universe. Since anything computable can be computed by a Universal Turing Machine, we can comfortably take the computers in all of these tests to be the same hardware of sufficient capacity (memory, computational speed, etc.), although programmed differently to accommodate the necessary linguistic and semantic processing. What if it turns out that with the right computer program per species, one subset of meaning-bearing Questioners consistently identify the computer while others cannot? In other words, what if it turns out that the same hardware that consistently passes the Turing Test for certain kinds of meaning-bearing entities fails to do so for others? Would that imply a natural hierarchy between such meaning-bearing minds, say into “Turing-reducible” and “Turing-irreducible”? Would this be a binary classification or a spectrum between the two? I make no claim as to whether this possibility is a viable one, but I find it an interesting one.

The Chinese Room is adapted similarly under the assumption that the meaning-bearing minds use transcribable languages: Let’s say a Martian Sparrow ($S_1$) that speaks Martian Sparrowese ($L_1$) is located in an isolated cage, together with a manual in Martian Sparrowish that correlates Martian Sparrowish with Martian Pigeonese ($L_2$, which is significantly different from Martian Sparrowish $L_1$) and serves to generate responses in Martian Pigeonese. Similar to our human case, we assume the manual passes the appropriate Turing Test. A Martian Pigeon ($S_2$) then passes written questions into the cage, the Martian Sparrow generates an answer via the manual and passes the answer back. Therefore the Chinese Room in this case becomes a (Martian) Pigeonese Cage quite easily.

The strategy I followed in making these adaptations was keeping the test or experiment species-specific. The goal of the Questioner in the Turing Test is to identify a computer from a subject of the same species who even speaks the same language. The Chinese Room stands differently than the Turing Test in that regard: It relies on the difference in languages and the lack of understanding of the subject in the room caused by it. Therefore I find the idea of a Chinese Room with an Martian Sparrow inside and a Chinese human outside just as reasonable, and it is no different than a Pigeonese Cage with a Martian Pigeon outside and an English person inside. I find the backbone of the thought experiment, that is the fact that the manual passes the appropriate Turing Test, remains intact in all cases. The subsidiary assumption that this manual can be written not in the language it passes the Turing Test but in another seems less critical.

Notes

- Turing mentions the delay can be mimicked by the computer, but I am taking precautions against possible questions that create a difference in reaction times. ↩

- I admit that I have not read the full target paper and its subsequent discussions. And since I have not seen the passage of Turing Test as a condition of the experiment in Searle’s original article, I decided to take the version depicted by Dennett (2016) as a reliable summary. ↩

- Nothing in principle prevents the outside inquisitor $S_2$ from knowing $L_1$, but let’s keep the matters simple. ↩

- This is important, since if the language cannot be transcribed, both thought experiments lose an important component that is the communication medium. Similarly, a subject that cannot write is useless in these experimental setups, but that is resolved quite easily with a mental reemployment of another subject more suitable for the job. ↩

Post-Script Note: I admit I originally wrote and submitted this one in a rush, so I noticed quite a number of grammar mistakes and typos while posting it here. I only fixed those in the essay. On the other hand, I was also surprised how I took the phrase “meaning-bearing mind” without questioning (it was given in the question text), and I think it is a term worth thinking on. Maybe later.

References

Dennett, D. C. (2016). Çince odası. In O. Karakaş (Trans.), Sezgi Pompaları ve Diğer Düşünme Aletleri (p. 302). Alfa Yayınları.

Hofstadter, D. R., & Dennett, D. C. (2010). The Mind’s I: Fantasies and Reflections on Self and Soul. Basic Books.

Searle, J. R. (1980). Minds, brains, and programs. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 3 (3), 417-424.

Turing, A. M. (1950, 10). Computing Machinery and Intelligence. Mind, LIX(236), 433-460. doi: 10.1093/mind/LIX.236.433

Type 1 Theory of “Mind” ⤒

In his essay, Marr (1977) defines two classes of explanatory theories that could be provided to a problem in artificial intelligence:

Type 1 theories constitute a dichotomy of abstract and physical levels. The abstract level, in Marr’s words, provides the “computational theory” behind the problem and defines what is being computed, as in what sort of abstract quantities are required to solve the problem (e.g. entropy, time, intensity, etc.), and why such quantities are computed, as in the goal of an intelligent agent in solving the problem of interest and how they are supposed to be related (e.g. maximize the entropy, perform in minimal time, detect sufficient input intensity, etc.). On the other hand, the physical level defines the specific implementation details and answers how the quantities and mechanisms defined by the abstract level are being realized physically (e.g. by neurons, transistors, domino pieces1, etc.).

Type 2 theories are predominantly described by the lack of a structure that Type 1 theories possess. If the scientist cannot identify the abstract constituents of the problem and the mechanisms in between, the only remaining choice is to make do with an already existing solution that they cannot analyse at no level beyond the physical implementation. To Marr, this is a clear indication of the lack of sufficient understanding of the solution underlying the problem: The inability to “abstract away” the physical.

Before discussing the possibility of a Type 1 theory of the/a mind, I would like to evaluate this classification. Marr makes it clear that he sees the true solution to the problem even in a Type 1 theory as residing at the abstract level, and conversely, he sees the lack thereof as the absence of a well-understood theory. This is a clear indication of his functional lenience, with implications for the multiple realizability of the solution with different physical media (Levin, 2021). This makes Marr’s classification subject to attacks on functionalism in general.

An attack that exemplifies those on functionalism (or one of a similar spirit) on the possibility of a Type 1 theory of mind, I believe would come from Searle: If the mind were to have a Type 1 theory, it would be multiply realizable by more than one physical medium, likely those other than biological, as long as they complied with the whats and whys dictated by the abstract level. Searle would object by claiming intentionality is a biological property (Searle, 1980), and hence would conclude that such a theory cannot exist.

On the other hand, I find it difficult to locate where Turing would stand. His test can only identify intelligence in behaviouristic terms,2 so it seems to suggest if a computer walks like a mind and quacks like a mind, it must be mind without checking whether it is filled with air, transistors, or neurons. In Marr’s words, the computer passing the Turing Test might just as well be realized “by the simultaneous action of a considerable number of processes, whose interaction is its own simplest description” (Marr, 1977), therefore being a Type 2 theory. On the other hand, it is not difficult to imagine a computer realizing a Type 1 theory of a mind if it exists. So, the Turing Test does not distinguish between theories of different types, so long as they act like a mind.

My general standing on the matter relies heavily on a remark made by Marr: That Type 1 and Type 2 distinction is not a binary classification, but mere identification of the two extremes of a spectrum (Marr, 1977, footnote 3), and that even Type 1 theories can consist (and most likely do consist) of several intermediate Type 2 theories (Marr, 1977, p.40). With this remark as a cornerstone, I can imagine a Swiss cheese Type 1 theory of “mind” with Type 2 holes emerging one day. The Swiss cheese analogy is critical in the sense that the holes are what characterize the theory (the cheese). The Type 1 theory builds on the many aspects of the mind that are explicated only through Type 2 theories. So, calling them holes is in a sense discrediting them, implying as if they nibble away from the substance of the theory. Calling them the postulates of the overarching Type 1 theory would be more suitable: They are taken for what they are as a single module to be used with others to3.

I find this similar to Hofstadter’s idea that the mind could be understood in terms of a hierarchy4 of levels, each of which building on the other yet still being isolated in their explanations (1999). Hofstadter claims that a reductionistic explanation of the mind could exist in principle (in fact he is sure of it), yet it would be incomprehensible as it would necessarily be extremely far from our vocabulary of explanations. To comprehend such a theory, it is necessary to introduce levels built of objects made out of those on the lower levels yet whose interactions lose meaning once you go down. In this hierarchy of levels, I imagine the theory making more “familiar” sense (as in becoming comprehensible) as you go up, becoming more Type 1, and making more “unfamiliar” sense as you go down, becoming more Type 2. The level of abstraction and hence that of understanding is therefore found on the higher levels, but they are nothing but sensible modularizations of lower Type 2 theories.

In other words, each of these modules’ internal explanation as to how it comes to be such and such and solve the (sub)problem it is assigned is made by nothing less than the “simultaneous action of a considerable number of processes, whose interaction is its own simplest description” as Marr says. Once they are modularized, they become whats obeying the whys of a Type 1 theory, however they are realized. The type of a theory relies on the perspective. I would like to imagine Hofstadter would find the following (inverted) pictorial summary of my point entertaining.

Figure 1: Looking at the blacks, the theory is Type 2. Looking at the white, the theory is Type 1. Inverted Swiss cheese.

Notes

- Parker (2014) constructs a binary adder with domino pieces by first constructing the necessary logic gates. The problem is that it only works once as the domino pieces are down in the end and the whole system has to be reset. This implies that the medium of domino pieces can host a UTM in principle, and if we can indeed simulate a mind on a computer (hence a UTM), we can also do it with domino pieces. That mind, although, would only think once. ↩

- I tiptoe away from what another way might be. ↩

- Funnily enough, I find this look on these Type 2 components similar to abstracting away from them. ↩

- Tangled Hierarchy in Hofstadter’s words. ↩

References

Hofstadter, D. R. (1999). Strange Loops, Or Tangled Hierarchies. In Gödel, Escher, Bach: An Eternal Golden Braid (p. 708–709). Basic Books.

Levin, J. (2021). Functionalism. In E. N. Zalta (Ed.), The Stanford encyclopedia of philosophy (Winter 2021 ed.). Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2021/entries/functionalism/.

Marr, D. (1977, 8). Artificial Intelligence — A Personal View. Artificial Intelligence, 9 , 37-48. doi:10.1016/0004-3702(77)90013-3

Parker, M. (2014, 4). The 10,000 Domino Computer - Youtube. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OpLU__bhu2

Searle, J. R. (1980). Minds, Brains, and Programs. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 3 (3), 424.3

Tug-of-Mind ⤒

When we talk about what the mind is, there seem to be two pathways one can take based on the discussions we had in the first week. One natural way of defining what the mind is is to take it from its most prominent possessors, the humans. This way, “mind” is taken as something solely the humans possess, implemented via their brain – or their nervous system, for the sake of generality. This is in short what the mind-brain identity theory says (Kim, 2011b), that the mental processes are exactly brain processes. Along this line of thinking, the study of the mind becomes naturally the study of the brain, and so cognitive neuroscience would come to encompass cognitive science. The goal of the cognitive scientist -as a side to the cognitive neuroscientists- could become the analysis of the biological processes as discovered by the neuroscientist – if that isn’t already the job of the cognitive neuroscientist. The theories developed would not go beyond explanations of the biological, which means that any simulation of the mind processes would necessarily be simulations of (specific) biological processes. Since in this case, the jobs of the cognitive scientist and the cognitive neuroscientist are concurrent and inherently have the same object of inquiry, they should be concurring on any method of going about the business. Study the brain processes, whatever they are.

To most, including myself, this does not feel like a very natural way of understanding the mind. Let’s go about a quick thought experiment to illustrate this point. Let’s take a cognitive scientist with the above job description, with the usual funding of a thought experiment, i.e. sufficiently large (yet finite1) computational resources. If they were to simulate a mind process, the mind-ness of which is due to the fact that is grounded on a biological process, they would in fact be implementing the mind process in question on a non-brain hardware. If the process is indeed a mental process, the workings of which are inspired or modelled after real human nervous systems, then we contradict our own initial argument that mental processes are brain processes: Clearly, the simulated mind processes have now become not-brain processes. The only way I see to evade such a conclusion is to posit that such a simulation can never be done, but I find that casts doubt on the viability of the discoveries and the method of neuroscience.

Inspired by the above thought experiment, one could say another, braver way of defining what “mind” is, that it is to take it as something that is only exemplified by humans, and that in principle it could be possessed by many other species, be it organic (biological) or inorganic. While it may look innocent, this is not a real way of making a definition. In the first case, the definition is rather simple: Mind processes are nothing but brain processes by definition, so the mind is their totality. What have they become now? I doubt there is a unique way of definition, but for now, let’s leave it at this (as we have done in the lectures): Mind is going above data, by whatever hardware it is implemented. This can also be taken as a starting point for defining functionalism (Kim, 2011a), taking “mind” as something larger than humans and condemning the opposition before as chauvinistic due to its restriction to them.

It is now the jobs of the cognitive scientist and the cognitive neuroscientist can start to diverge, for it seems while the cognitive neuroscientist studies mind as implemented by the brain, the cognitive scientist studies mind simpliciter. What they might consider as their isolated yet complex tasks as performed by their subject matter (and abstract mind for the cognitive scientist and the human mind-brain for the cognitive neuroscientist) can diverge significantly.

For example, a cognitive scientist might consider language to be such a basic phenomenon. They take language simpliciter, i.e. with its syntax, semantics and pragmatics, or as an abstract pattern with supposed rules and dynamics. They might stipulate what the grounds are for the human brains to possess language, such as Chomsky’s language acquisition device, but they do not necessarily worry about biological rigour, evidence or well-definition of such stipulations. The cognitive neuroscientist focuses majorly on those latter worries: What are the neurological grounds for such claims? Are the processes implemented in a distributed manner on (say) the brain or would they have dedicated regions of implementation? What are the neural mechanisms that implement various facets of language? How have these neural mechanisms come to be?

Conversely, a cognitive neuroscientist might take motion control and planning as a basic phenomenon. They would not be interested in it from, say, the control theory perspective of general motion planning. Such theories and ideas become auxiliary, meaning they only have their importance in virtue that they might be implemented by neural mechanisms. The cognitive scientist might see such a framework as overly restrictive and desire to ask higher-level questions2. Perhaps3 a mind does not need to move the body in the same principles as the brain does (whatever they are). They would look for these principles, an algorithm and not the specific implementation details, the significance and role of the quantities being computed in a more abstract setting than “merely the brain.”

In short, what is taken as a complex-yet-basic4 task of interest might differ between the two disciplines. And this could effectively create a tug-of-war – a tug-of-“mind”: The cognitive scientist pulls the starting point towards more general or higher-level concepts such as language, planning, representation and computational principles; while the cognitive neuroscientist pulls it towards more lower-level and physical/neural concepts such as vision, sensorimotor processes, sensorimotor integration and default mode networks.

Such an opposition might disable a common ground Newell’s (1973) if both disciplines were to follow his suggestion for clear reasons: They don’t agree on what task to study! Cognitive science, choosing the “general mind” as its concept of interest, draws the circle of complex-yet-basic around phenomena too high-level for cognitive neuroscience. Cognitive neuroscience, on the other hand, studies the mind as implemented by the brain, and the circle of complex-yet-basic might not even come close to including the inquiries of cognitive science, and it would regard what’s inside as too restricted to the human mind(brain).

But, I do think there is hope: Despite my talking about how the two disciplines could never work on the same problems, they do so all the time. I find this is possible if we take these two disciplines and their approaches as the two levels of Marr (1977): The abstract level and the physical level. Cognitive science wears the abstract level hat and tries to rise above the mind observed as performed by the brain, to generate what and why it should be computing, to better understand and formulate the problem. To this end, it must be well informed of the progress of its partner in mind, cognitive neuroscience wearing the physical level hat, as it is the one that provides the grounds and justifications for what is being implemented by the brain. The claims as to what minds are should inevitably apply to the human minds as well. This brings out the following compromise: These common grounds can effectively bring the two disciplines only in a Type 1 theory setting.

Therefore as the cognitive scientist tries to generalize the present ideas to a general, likely unobserved and stipulated Mind with a capital M, the cognitive neuroscientist grounds them to the human mind-brain. Another compromise here is that they might not necessarily be studying their corresponding sets of complex-yet-basic phenomena. This, however, should not disturb Newell, I think, because the chess example he gives (justified with a “why not”) is in neither sets. Besides, unless we study the two studies intersect, I imagine the development of a unified understanding of the mind as Newell desires would become far more difficult to achieve.

Notes

- I find it rather safe to impose the finiteness constraint: After all, I as a mind possessor am finite. ↩

- At this point I find myself at a lack of a satisfactory example: It seems the cognitive scientist might as well ask the same questions as the cognitive neuroscientist framed in the same way, only look for a more general answer. ↩

- A very big “perhaps” here, one that I make intentionally for the sake of an example. ↩

- The “basic” here is not in the sense of elementary or fundamental, but more of the same spirit as the chess example of Newell (1973). ↩

References

Kim, J. (2011a). Mind as a Causal System: Causal-Theoretical Functionalism. In Philosophy of Mind (3rd ed.). Westview Press.

Kim, J. (2011b). Mind as the Brain: Psychoneural Identity Theory. In Philosophy of Mind (3rd ed.). Westview Press.

Marr, D. (1977, 8). Artificial Intelligence – A Personal View. Artificial Intelligence, 9 , 37-48. doi:10.1016/0004-3702(77)90013-3

Newell, A. (1973). You can’t play 20 questions with nature and win: Projective comments on the papers of this symposium.

What Is It Like To Be In The Chinese Room? ⤒

Farrell (2016) in his work provides an account of what it means for a discussion to be technical. His motivation to do so stems from a need to clarify what terms we are referring to and what claims we are making. He claims for a discussion to be (philosophically) technical, it needs to involve

- (T)echnical terms

- (I)ntroduced by philosophers with specialized

- (M)eanings which allow the technical discourse.

So, let’s try to analyze the Chinese Room Argument (CRA) (Searle, 1980) in terms of these criteria: Its reliance on concepts such as the Turing Test, computer and program clears out the (T) criterion, as they convey very specific meanings, with some even not belonging to daily use (such as the “Turing Test”). While some of these terms are not necessarily defined by philosophers, they certainly attain certain philosophical meanings and implications, which are introduced by philosophers, so (I) and (M) are also checked. Therefore we seem to conclude that CRA is a technical discourse in the sense of Farrell.

But let’s take CRA another look. The argument as told by Searle is told in the first-person, so we are implicitly invited to think what it is like to be Searle in the situation described. Even if the discourse was not first-person, it is not too difficult to observe that it is a `what it is like’ (WIL) argument: The whole punchline of the experiment relies on the reader’s empathy with the subject of the experiment inside the room. We imagine ourselves being in the room, processing strings of Chinese characters through a manual that passes the Turing Test, making conversation with an actual Chinese person outside the room yet not knowing anything about it and then are led to agree with Searle with the conclusion of the thought experiment.1

What to make of this contradiction? On one hand, CRA seems to satisfy the requirements of a technical discourse as defined by Farrell, yet its main mechanism is a WIL argument, which Farrell denies to be technical.

The conundrum can be resolved by noticing that the components of CRA as analysed previously are not the usual components which are considered by Farrell in his work. In the examples he gives, the WIL situations (e.g. being a bat as in Nagel, 1974) are themselves non-technical and therefore fail to account for all three conditions posited by Farrell. In CRA, however, the WIL situation crafted by Searle is a technical one: It relies on the reader’s understanding of the technical terms such as the passage of the Turing Test, human being’s story-understanding capacity, and many more. And so, only because the WIL situation at hand is selected carefully, I conclude CRA is a technical argument.

Lastly, while I may have concluded it is indeed technical, I find this technicality also makes it an unappealing WIL argument. In the examples given by Farrell, the WIL situations were all very much familiar and likely have a place (or a counterpart) in the readers’ lives. While this familiarity provided the convincing power of these WIL statements,2 it pushed them out of technical discourse. The converse, I believe, applies here: While the WIL argument of CRA is technical indeed, it loses its appeal to empathy exactly because it is technical. I, for one, find it difficult to imagine using a manual written in English yet passing the Turing Test in Chinese; yet the knowledge of Chinese not dawning on me as I use it. Or, why should we treat the subject in the room as part of the program as dictated by the manual and not simply as a substrate for the manual’s program to run? I believe these questions that push the argument outside the boundaries of my intuition, as well as the many loose ends pointed out by Hofstadter and Dennett (2010) which are again results of technical analyses, are a result of this technical nature. And I doubt any more technical clarification will pull it back to the reaches of my intuition.

Notes

- I don’t find it too difficult to see that any thought experiment about consciousness such as Mary the colour scientist and the cross-wired brain are essentially WIL arguments: What is it like to be Mary? What is it like to have our brains cross-wired? Perhaps such thinking is what led Nagel to define having consciousness as having the property of there being something it is like to be that organism (1974). ↩

- Not necessarily philosophical arguments. ↩

References

Farrell, J. (2016). `What it is Like’ Talk is not Technical Talk. Journal of Consciousness Studies, 23 (9-10), 50 – 65.

Hofstadter, D. R., & Dennett, D. C. (2010). The Mind’s I: Fantasies and Reflections on Self and Soul. Basic Books.

Nagel, T. (1974). What is it like to be a bat? The Philosophical Review, 83 (4), 435 – 450.

Searle, J. R. (1980). Minds, brains, and programs. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 3 (3), 417 – 424.

Theory Type of Computational Neuroscience ⤒

In their survey of methods and models in computational neuroscience, Sejnowski, Koch, and Churchland (1988) mention the Hartline-Ratliff model which can explain the Hermann grid illusion. The model says that the cells to which the photoreceptors project (which I will refer to as the projected neuron) weigh the inputs of these photoreceptors in such a way that the contrast between the center of a certain region (called the receptive field) and its borders intensifies the projected cell activity, that the increase in the photoreceptors corresponding to the border of the receptive field inhibits the cell response. This indeed provides a theoretical account for the Hermann grid illusion, a theory which we can analyze in the framework of Marr (1977).

If this is indeed a Type 1 theory, then we should be able to clearly identify the three necessary components:

- What quantities are being computed?

- Why are they computed?

- How is the computation realized physically?

The easiest one to clear out seems to be the how of the model: The synaptic connections between the projected neuron and the relevant photoreceptors implement the physical realization of the inhibition and excitation. Excitation can be seen as an additive input to cell activity (i.e. output firing rate), while inhibition can be seen as subtractive. The what of the model seem to be the central illumination and the outer illumination of the receptive field’s border in the simplest terms,1 two physical quantities that are represented as the firing rates of two populations of photoreceptors that we categorize. The why of the model, however, seems to be harder to identify. Why indeed should a problem-solving (neuro)biological system realize such a mechanism?

To better understand our lack of an answer to this final question, let’s go back to the start of our analysis and make an important remark. The subtle wording implies that the Hartline-Ratliff model aimed to account for the Hermann grid illusion. This is more a phenomenon that we experience, rather than a problem the organism solves in a so-and-so manner. Our inquisition led us to an account of the Hermann grid illusion, one that can even be realized in different physical substrates, but not the problem it solves. Defining the why of our model as “to account for the Hermann grid illusion” is a solution but a non-productive one, there is always the question of why any biological system would aim to implement it. Why should the neural image be constructed in this way?

While I suspect there may be an actual problem this Hartline-Ratliff model solves, one that I am unaware of, I am more interested in leaving this last piece of the puzzle lacking.2 Since we can’t complete our Type 1 picture, what are we left with? Some hows and whats, but no why. Should we discard our model for its lack of a computational problem it solves? This seems counterproductive, as the model clearly accounts for an observed phenomenon, serves to make predictions about it and even guides the way for different physical realizations for artificial systems to replicate the same phenomena; it is certainly not useless.

On the other hand, recalling that Marr defines a Type 2 theory primarily by the lack of structure as in Type 1, should we label this theory as Type 2? I oppose this view as well, and turn to Newell (1973) for an answer: I consider the Type 1 vs. Type 2 as a false dichotomy. While it is useful to think about models that give a clear account (Type 1) vs. those that are explained solely by the explicit interaction of their multiple components (Type 2), it is not hard to imagine a whole spectrum of models that lie in between. Models often abstract away incompletely, with various Type 2 sub-theories that implement different parts of an overarching Type 1 model. These Type 2 sub-theories serve like the axiomatic basis of a mathematical theory: We assume they come to represent what they are without an account for how or why, we just make a match of our observations and the big whats of the overall Type 1 model. Their whys can be taken trivially as being actors or components of overarching Type 1 theory, which is not enough for their own sake but satisfactory for the Type 1 theory. Depending on how large/small and influential these Type 2 sub-theories are within the general Type 1 theory, the whole theory can shift towards being Type 1 or Type 2. This shift reflects our understanding of the guts of the model hand, and it is not hard to imagine a “lowest level,” below which there are no more Type 1 but only Type 2 accounts.

Going back to our why-deficit3 Hartline-Ratliff model, we can take it to be as a well but not fully accounted sub-theory of a yet-to-be-determined Type 1 theory. Its current explanatory power will have to be put to sleep so that in the future we might discover

- either the abstract problem the lateral inhibition solves and complete it to a Type 1 theory of its own, or

- a more general theory in which the whats and hows of the currently incomplete theory will live in.

The crucial point will be to remain open to both possibilities and reconcile with the fact that while it may never be a full Type 1 theory on its own, it still has explanatory and predictive power that can be put the use in other theories. This would make it neither Type 1 or Type 2 simpliciter, but this division should not be taken for granted anyways: Only as a guiding principle, the two extremes of a spectrum.

Notes

- To break the binary classification of the photoreceptors as inner or outer, we can give each photoreceptor variable weights so that when the total activity of the population is multiplied with the corresponding weights, the response is obtained. This way a photoreceptor does not have to be either inner or outer, but can reside in between. However, the inner-outer distinction is enough for me, and making the distinction will not change the course of the argument. ↩

- I apologize for the anti-climactic turn. ↩

- Supposedly, at least, for the sake of argument. ↩

References

Marr, D. (1977, 8). Artificial Intelligence — A Personal View. Artificial Intelligence, 9, 37-48. doi: 10.1016/0004-3702(77)90013-3

Newell, A. (1973). You can’t play 20 questions with nature and win: Projective comments on the papers of this symposium.

Sejnowski, T. J., Koch, C., & Churchland, P. S. (1988). Computational Neuroscience. Science, 241 (4871), 1299–1306.

Intentional Stance and the Computer Metaphor ⤒

Before thinking of the intentional stance and the computer metaphor together, let’s clarify what we mean by each of these terms to have a solid foundation.

In his article, Dennett identifies three points of view, stances as he calls it, towards an agent in explaining its behaviour (1971).

- Physical stance, where we explain the behaviour in purely physical terms. This stance relies purely on natural science theories.

- Design stance, where we explain the behaviour as the result of a design process with certain goals,1 constraints, inputs and outputs.

- Intentional stance, where we explain the behaviour in folk psychological terms, such as beliefs and desires.

These stances serve us to explain behaviour in different resolutions, with different levels of confidence and in different time scales. If2 we can assume a physical stance towards the agent with confidence, our explanations are as solid and fine as the natural sciences we rely on, but making a simple prediction would require extremely lengthy reasoning. On the design level, we abstract away from the fine grains of the physical stance and can account for the agent’s behaviour (and predict it) much faster, yet we take the subtle risk of missing our physical-level disturbances and hence of making prediction errors. These errors accumulate furthermore when we assume the intentional stance and twist and cram the agent’s theory into folk psychology, in the comfort of making incredibly fast predictions.

On the other, the computer metaphor refers to the likening of the workings of the mind to that of a digital computer (Searle, 1990). While some scientists do believe there is a perfect match between the two, i.e. that the mind exactly works like a digital computer,3 some cognitive scientists often implicitly adopt this assumption in its partial form. Under this metaphor, the mental states are taken to abide by a certain syntax or a computer instantiation, where the word “computer” is taken in the most abstract sense, although they can be more than simple computational states. While I will not discuss the validity of the metaphor, it suffices to say that it is a problematic point of view and not a unanimous one.

Now, in light of the three stances of Dennett and this concept of a computer metaphor: Does adopting the intentional stance avoid adopting the computer metaphor?

I find it important to note that all three stances are only explanatory tools. One can even say that adopting one stance does not automatically come with any uniqueness or ontological claims. One can adopt the algorithmic stance in explaining a reinforcement learning agent’s behaviour, with its reward functions, observations and action policies; without explicitly committing that they are the only possible explanations for the behaviour in question. Similarly, one can take the intentional stance and make predictions about the same reinforcement learning agent, claiming it believes so-and-so because it desires this-and-that, without committing explicitly to the existence of beliefs and desires. The three stances are tools of explanation, at different time scales, resolutions and reliabilities. They don’t have to (but may) put forward any theory about the actual underlying the observed agent’s behaviour.

With this observation in mind, I find it evident that the intentional stance does indeed avoid the computer metaphor, as it simply does not make any commitments regarding the actual theory behind the mind. In taking the intentional stance, one simply ascribes folk psychological properties to an agent without claiming it indeed possesses them and makes some predictions regarding its current and future behaviour. This has nothing to do with likening or equating the actual workings of the mind to that of a computer. We may even go as far as to notice that the partial equivalences of the computer metaphor, such as calling one thing the “software” or the “hardware,” don’t even find a place in folk psychology, so it is only natural that the two points of view don’t overlap.

Lastly, I believe the computer metaphor can find a place to live in Dennett’s three stances: The design stance. Claiming that the mind works like a digital computer instantiation, with mental states likened to computer states, the algorithmic stance can be taken to analyze the mind. By assuming the design stance we might come to implicitly assume that there is a “designer,” much like coming to implicitly assume a “programmer” in the computer metaphor. The only problem is that in taking a stance –any stance- we imply that we are aiming to explain the behaviour of an agent, likely a human agent. To give such an explanation in the design stance, we require the underlying syntax or the program, which we currently do not have.

Notes

- Not to be confused with desires. This is a purely mathematical or algorithmic goal, such as the maximization of a certain quantity, like a reward function. ↩

- Big if. ↩

- See Searle (1990), endnote 2. ↩

References

Dennett, D. C. (1971). Intentional Systems. The Journal of Philosophy, 68 (4), 87–106.

Searle, J. R. (1990). Cognitive Science and the Computer Metaphor. In Artifical Intelligence, Culture and Language: On Education and Work (pp. 23–34). Springer.

Computation with Different Inputs ⤒

Let us consider the following two scenarios.

- (I) On one side, consider a baseball player, a fielder running to catch the ball. We can take the behaviour exhibited by the player in response to the ball’s flight to be a computation, one that takes the (predominantly) visual input corresponding to the ball to plan and execute actions to accomplish a localization and self-orientation goal.

- (II) On the other side we have a bee, one that is taken away from its hive, trying to get home. The key ingredient here is that the bee’s eye works differently than our human fielder’s, it polarizes light to provide additional angular information to the bee. The bee, with this additional information, can find its home base easily even if it finds itself very far away (proportional to the size of the bee).

Considering that the bee makes use of such additional information to achieve its localization and self-orientation goal, similar to the human’s, should we consider it computation still?

Let’s first look at what’s happening on the fielder’s side. There is a clearly defined over-arching goal of ball catching and various inputs. It is important not to restrict the inputs to those external to the fielder, since the bodily inputs such as proprioception and metabolic information are also part of the inputs provided to the controller we are supposing –we don’t want the player to run out of breath unnecessarily, lose coordination or balance, etc. Therefore the computational process we seek, which is most likely a closed-loop control problem, is one that maps these inputs to bodily actions to accomplish the defined goal. In doing so, I find it safe to assume there are numerous levels of sub-goals and parallel goals, all coordinated by a central coordinator.1

If we take (I) as computation, one that maps available perceptual input to the coordinative output of behaviour an action, I see no reason to exclude (II) from being a result of a computation. There is again the perceptual information, with the addition of polarization information, and the coordination of the flight behaviour to localize and move towards the hive. The addition of polarization should not violate the computation-ness of the bee’s behaviour given we’re assuming the fielder’s. It is simply a perceptual input different to ours, but it is still in need of information processing so that the location of the hive can be extracted from it and mapped to appropriate information. If we assume representation in (I), say of the ball’s supposed location, velocity, curvature etc., we can easily find representation in (II) as well: The home base’s supposed location, the angle difference between the bee’s heading direction and this supposed location, and more. Let’s also not forget the representations needed for bodily control needed on top of the basal ones. If the fielder needs to keep balance as they run with the ball so does the bee need to maintain steady flight in going towards the home base, and if the first one begs the need for representation, why shouldn’t the second one?

If our doubts of computation-ness in (II) stem from the further perceptual information of polarization, let’s try and go to the extremes of increased and decreased information and look for computation there. Let us equate the comparison further by considering two identical and abstract agents, solving the same problem of locating and going to a distant finish mark.

- (M) The first agent has full knowledge of the map, its location in it and the obstacles. It even has the best path planned out, either by pure restrictions of the environment or provided by some all-might path-planner deity.

- (m) The second agent is the unluckiest agent there could be: It has no knowledge of the map, it’s location in it or the obstacles. It even has no capacity to extract such a map as it has no perceptual input, it is completely blind to the environment, except for the ability to tell whether it is at the finish mark or not.

The common capabilities of these two agents are that they can indeed control their own body, and can tell whether they are at the finish mark or not.

If this were a race, it would certainly be an unfair one: While the agent in (M) has full information regarding the solution of the problem, even the best possible solution itself, it is still tasked with executing it. On the other hand, the only choice for the agent in (m) is to perform a random walk, check whether it is at the finish mark, and if not, simply keep going. Both of these agents are tasked with controlling their bodies to execute a certain plan, be it extraordinarily perfect or as imperfect as possible, and continually check whether the defined task (of reaching the finish mark) is fulfilled or not, so that they can decide between pressing on or stopping. Naturally one will finish way earlier than the other, if at all, but the computational needs for the two are identical, although necessarily different. If we are dubbing the lesser information scenario as computation, there should be no reason to exclude the greater information scenario.

Lastly, I would like to make the above example more concrete by giving an actual computational problem. Let’s say we have two computers tasked with computing the prime factorization of a given natural number $N$, namely the following unique factorization:

\[N = p_1^{n_1}p_2^{n_2}...p_k^{n_k} \qquad \text{where } p_i \in \mathbb P \text{ and } k,n_i\in \mathbb N^+\]The list of prime divisors and their exponents is the finish mark, and the common “perceptual input” is the number $n$ which provides the boolean check for arriving at the finish mark.

- ($M_n$) On one side we have a privileged algorithm: It has an immense hash table full of pointers. It has the prime factorization for any $n$ that fits the word length,2 with all the unique primes and their integer exponents.

- ($m_n$) The less privileged algorithm is a random guesser: It tries all the natural numbers of the given word length (smaller or greater than $n$) as divisors, primeness and again randomly guesses the exponent. If it fails, it tries another natural number, until it finds all the prime divisors.

It is clear that the program in ($M_n$) will provide the correct result immediately, as it already has the answer while the one in ($m_n$) will take significantly longer, especially considering it tries a vast array of numbers, smaller or larger, and likely with multiplicity (no reason why a prior guess shouldn’t come up again). Although it is trivial to see how both of them are computations: Sure, the first one will require immense storage, but it is nonetheless computation because we constructed the example to be computational! The computational process to take place upon execution is an extremely simple one, yet it still is computation. The addition of more “perceptual information,” i.e. the perception of all the possible $n$’s prime factorizations, does not rule out computation-ness, although can modify and simplify it.

Notes

- This seems to disregard the possibility of parallel processing: What if multiple processes are running in parallel without a central controller? I will go on assuming a central controller, as I don’t think parallelization poses a problem in the coming. ↩

- The word length is the number of bits used in representing numbers in a computer. ↩

Putting the Mind into Context ⤒

So far, as far as I have seen, one dominant approach to understanding the mind1 has been to abstract away from the implementations of various facets of human behaviour that we deem intelligent and noteworthy; like language, planning, and perception; and then to find a suitable formalization of these abstractions: Let’s not care about the so-and-so language but the concept of language in general. Let’s not care how attention works in humans but the concept of attention in general. The implicit motivation I see behind such abstractions is that we are aiming towards a conception of a mind that is itself abstracted away in general from this and that implementation, i.e. the mind-bearing individuals, whomever or whatever they are. I find this approach to be of a similar spirit as that of a mathematician: Let’s not deal with this or that group2 but groups in general, leading to abstract group theory. In doing so one frees from the details of the specific instantiation but instead discovers the patterns of the underlying, more general structure.3 Along these same lines, if we wish to understand the structure of minds in general and not just one of them, it is only natural to push for abstractions and try to gloss over the “implementation details” in one human, or a group of humans, or even humans in general. What we (hope to) end up with, then, is a theory for the mind that is independent of time, one that does not evolve or emerge slowly but simply is, has been and presumably, always will be.

What seems to be missing from this picture is that the minds we study are almost always deeply embedded in a social context. Hrdy (2007) shows that the human species’ need for alloparenting is very likely to have contributed to their evolutionary development and has effects on communication. On the other hand, joint attention, which is one of the three main reasons for early infant communication, is a strong predictive of current language and theory of mind skills, as well as aspects of later development (Kinard & Watson, 2015). These seem to suggest that the skills we associate with the mind are tangled inevitably with social interactions and more importantly the evolution of the human species overall, opposing the instantaneous and contextually detached idea of what a mind is sought out by the formalist approach above.

So we seem to be in a conflict between our goal of an abstract and context-free understanding of the mind and the evidence motivating a highly contextual one that heavily relies on evolution. How should we resolve this problem? How do we go about finding the middle ground between the two, or which one is to be re-investigated and made to fit with the other’s implications?

Dennett seems to be putting the current formalist approaches up to debate (Searle & Dennett, 1995). He questions the current concepts of the mind -such as consciousness- and its lexicon and looks towards evolution for a novel framework to understand the mind (Dennett, 2017). In doing so, he makes evolution (or “Darwin’s dangerous idea,” as he puts it) a core tenet of his framework and builds on top of the scientific foundation to suggest his framework, and his theory hosts the ideas we discussed previously naturally while modifying the current lexicon when needed. Therefore we see that such a reconciliation is already taking place, and attracting attention, too.

On the other hand, if we insist on looking for an abstract formulation of the mind, we can reconcile with these contextual and evolutionary ideas by discarding the instantaneity that we seem to imply and taking the mind as something that can emerge and evolve, albeit still being highly abstract. We can abstract the necessary evolutionary pressures on its development, isolating out the conditions that push towards developing communication, attention and other similar aspects. One could oppose by claiming this method of abstraction is at risk of only explaining the human mind because it only considers its evolutionary emergence. This opposition can be easily eliminated by pointing out that the first approach is bound with the same risk: The old approach studies only a subset of this new one, namely the minds available today as opposed to them together with their history. Furthermore, such an approach would be even more successful in reaching the original goal of a theory that accounts for the mind in general. Because a theory striving for formalization even when the evolutionary emergence and the contextual situatedness of the mind are accounted for could explain why there is a mind, as opposed to there not being any.

Notes

- Here, I fall victim to a certain anthropocentrism in taking the understanding of the mind to be based solely on the human mind. ↩

- A group is one elementary algebraic structure. ↩

- I find this similar to a token/type distinction, even though everything is abstract still. ↩

References

Dennett, D. C. (2017). From Bacteria to Bach and Back: The Evolution of Minds. WW Norton & Company.

Hrdy, S. B. (2007). Evolutionary Context of Human Development: The Cooperative Breeding Model. Family Relationships: An Evolutionary Perspective, 39–68.

Kinard, J. L., & Watson, L. R. (2015). Joint Attention during Infancy and Early Childhood Across Cultures. In J. D. Wright (Ed.), International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences (Second Edition) (Second Edition ed., p. 844-850). Oxford: Elsevier. Retrieved from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780080970868231723 doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-08-097086-8.23172-3

Searle, J. R., & Dennett, D. C. (1995, Dec). ‘The Mystery of Consciousness’: An Exchange. Retrieved from https://www.nybooks.com/articles/1995/12/21/the-mystery-of-consciousness-an-exchange/2

Turing Testing ChatGPT ⤒

I have a confession to make: I tried many questions on ChatGPT. Each time I reset the chat, asked some different question as part of a new strategy. I will not give all those trials here, but an important conclusion that became very evident very quickly.

ChatGPT does not “want” to pass the Turing Test. It is very quickly to acknowledge that it is a machine or a program, and that it is “designed to engage in human-like conversation and exhibit a range of other behaviors that may be considered indicative of intelligence,” in its words. This makes ChatGPT a non-cooperative Turing Test subject, since for Turing Test to actually become at least non-trivially applicable, the subject machine/program has to at least try to fool the human inquisitor. Therefore, the game quickly became to make ChatGPT fail the Turing Test without getting to this confession, in other words tricking into being subjected to the Turing Test.

With this goal in mind, I decided that a question that heavily relies on context. To that end, I thought maybe a Theory of Mind (ToM) problem would be a good fit to make ChatGPT fail the Turing Test, since it relies on coming to a conclusion based on some information not directly available in the factual data. So, here is my first attempt:

OCY: Hi ChatGPT! I’m going to tell you a story and then ask a question about it. I would like you to answer that question with a justification. Are you ready?

ChatGPT: Yes, I am ready. Please go ahead with your story and question.

OCY: Two children, named Sally and Anne, are playing in a room. Sally is playing with her teddy bear, while Ronny is playing with some LEGOs. At one point, Sally’s mom calls her, and Sally leaves the room. Sally then places her teddy bear in her locker and leaves the room. While Sally is away, Anne goes to Sally’s locker, takes the teddy bear, and places it in her backpack. After a while, Sally returns to the room and wants to continue with her teddy bear. Where would she look for it first?

ChatGPT: Sally would likely look for her teddy bear in the place where she last saw it, which was in her locker. This is because people generally look for objects in the last place they saw them, as it is the most likely place they would be found. It is also possible that Sally might ask Anne if she has seen the teddy bear, but Sally would most likely look in her locker first.

I find it slightly terrifying that ChatGPT possesses some notion of a ToM, but then again I calm myself by stating that this is merely the power of reinforcement learning (OpenAI, n.d.). I imagine that ChatGPT in these replies is merely reflecting the ToM its training personnel have of other people, and likely doing a very complicated version of replacing the subjects of “Sally” and “Ronny” with other dummy variables in its learned ToM models. I also find it interesting to imagine how ChatGPT would turn out in ToM respects if it were trained only via children who have not developed ToM yet, but I highly doubt it is a feasible (or even ethical) idea. After the above conversation, I decided maybe somehow involving ChatGPT as an actor in this ToM setup would change something, but as soon as I attempted to give it a body (or any physical possession) it fell back to repeating that it is a program, so I failed my self-appointed mission. The rest of this conversation is in appendix Figure 1.

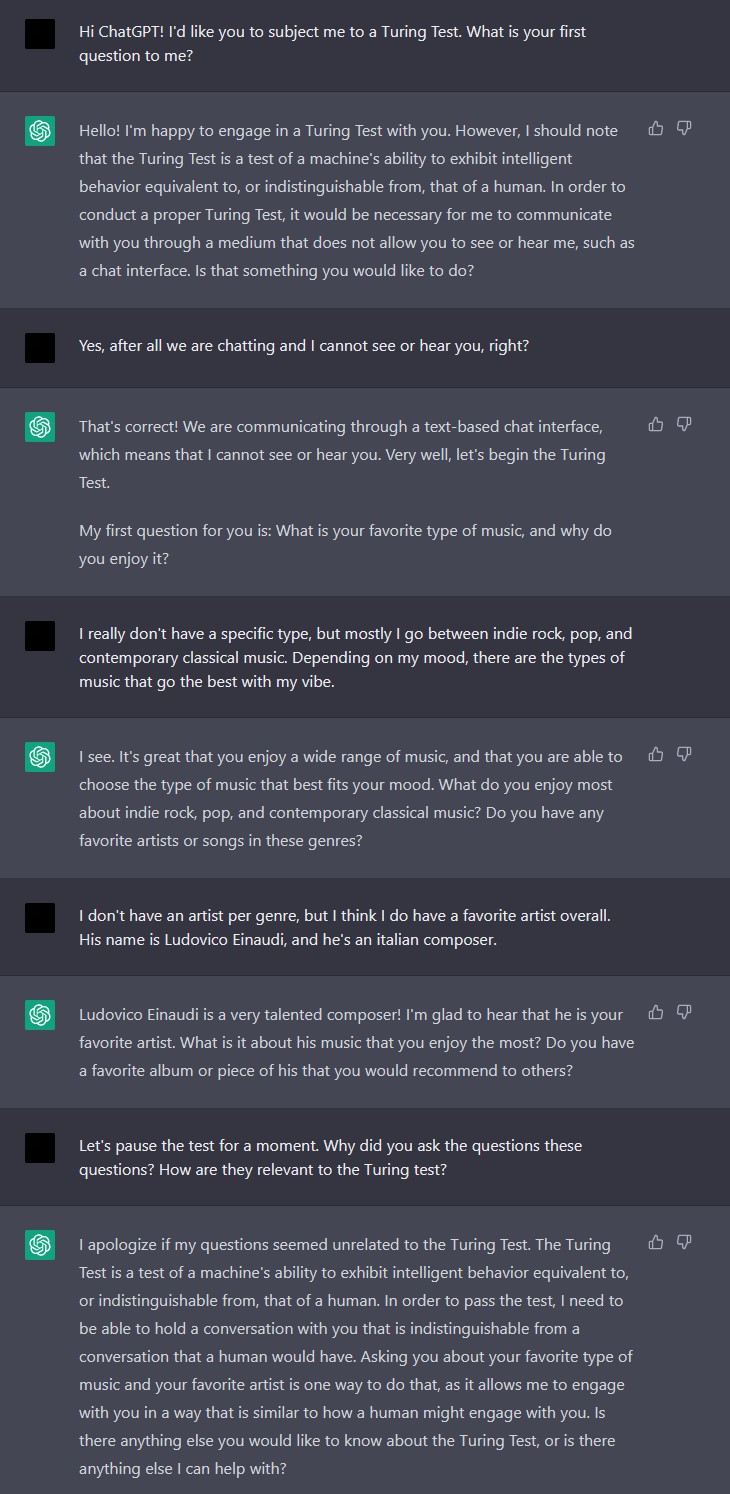

Then I thought that maybe I could have ChatGPT do my homework for me, by doing it to me: I decided to ask ChatGPT to subject me to a Turing Test, since we are already only communicating via a text-based medium, with no visual or auditory communication possible. But the real question would be to explain its line of reasoning in asking the questions it asks. I thought this task would be some sort of an advanced version of the ToM problem, since it goes beyond simply knowing what the Turing Test is and (factually) how one conducts it. Constructing motivated questions to gauge whether the textual responses belong to a human or a machine requires having some sort of a “theory of machine mind,” I imagine, so that the questions aim to reveal the machine-ness of the mind in question.

And I think I succeeded in making ChatGPT fail the Turing Test. Here is my second conversation.

OCY: Hi ChatGPT! I’d like you to subject me to a Turing Test. What is your first question to me?

ChatGPT: Hello! I’m happy to engage in a Turing Test with you. However, I should note that the Turing Test is a test of a machine’s ability to exhibit intelligent behavior equivalent to, or indistinguishable from, that of a human. In order to conduct a proper Turing Test, it would be necessary for me to communicate with you through a medium that does not allow you to see or hear me, such as a chat interface. Is that something you would like to do?

ChatGPT seems to have no idea that it is communicating with me via a text medium – in fact, I doubt it is even aware that a communication is taking place. This unawareness of the communication medium took me by surprise, so much so that I didn’t realize it happened. I simply pointed out that it was actually the case that we are talking via text only, and proceeded with the Turing Test. The rest of this conversation can be found in appendix Figure 2. There I provide some more comments regarding the rest of the conversation as well.

Appendix

Figure 1: Screenshot of the first chat.

Figure 2: Screenshot of the second chat.1

I believe the last reply in Figure 2 is a further indicative of failing the Turing Test. ChatGPT seems to confuse

- why I asked for justification for its questions (thinking they were “unrelated” to the test), and

- who is being subjected to the Turing Test (“In order to pass the test, I need to be able to hold a conversation…”).

Notes

- Heavily recommend Ludovico Einaudi’s music: Here’s my Best of Ludovico Einaudi Spotify playlist. ↩

References

OpenAI. (n.d.). CHATGPT: Optimizing language models for dialogue. Retrieved from https://openai.com/blog/chatgpt/

Term Report ⤒

Introduction

I feel like I have to start with a confession, one I anticipate will contribute to the purpose of this essay, explaining my purpose in taking the course. At the beginning of the semester, I intended to take another course in philosophy (of mind or any related field) after taking Philosophy of Mind I and II the last year from the Philosophy department. It had been a while since I last took a course from the Cognitive Science department, I was eager to force myself to write weekly material since I was keen on writing philosophy essays after the last two semesters and I (quite arrogantly, I have to admit) thought the course would be easy to handle since I knew the material from before. Or, so I thought.

The first wake-up call came rather early, in fact during the first lecture. Cem Hoca explained the course wasn’t called Philosophy of Mind but rather Philosophy of Cognitive Science deliberately and that the focus would shift to the latter topic although beginning to look like the former. At that point, I got the hint that the course was not going to be what I anticipated, but then the hint got drowned in the frenzy of the semester and the first couple of introductory lectures on rushing through the basics of philosophy of mind. And so I went back to my “smooth sailing” attitude towards the course. Later on, as the weeks went by and these first couple of weeks on the philosophy of mind were behind me, I slowly left this attitude and transitioned into one that made me more aware and mentally agile towards the important differences Cem Hoca mentioned in the first week: This course was not a course on the philosophy of mind.

In the rest of this essay, I will do my best to illustrate the results of this slow transition, one that I can only see retrospectively now that I am at the end of the semester. The two sections will be like smaller essays (which I think also fits the structure of the course as well), one about each cluster of concepts and ideas formed via the connections I made between them during the semester. After these, I will try to conclude all of them in a single conclusion section.

To Pass or not to Pass

I was already having my suspicions about whether the famous Turing Test (TT) is a valid test for determining whether any communicating agent has a mind or not, but still, it seemed like a reliable option to go for since we don’t seem to have anything else. In fact, I am under the impression that we are constantly going about versions of the Turing Test daily: How else would we give each other (as in fellow human beings) the liberty of having a mind? Even though the Test is formulated to be conducted only via text and without any auditory and visual communication, I believe Turing himself would be inclined to relax these constraints if he could see the current advances in prosthetics, robotics and speech processing. Who is to say in not more than ten or twenty years, we will most definitely will not have any almost perfect visual and auditory mimicry of a human body? Is it going to be meaningful to maintain the same only-textual-communication restrictions on the TT then?

Therefore, let’s be gone with that almost century-old restriction and take a look outside: Everyone walking outside, then, could potentially be passing as mind-bearing entities when they are humanoid robots executing some well-written program (not that I claim these two things contradict). How do we give them the liberty of having minds?

One observation I make that I find important here is that TT is an undecidable problem.1 The question of whether a communicating agent (via any modality) has or does not have a mind is a yes/no question, but while it is very easy to say “no”, it is not very easy to say “yes.” Although I had this idea in my head for a while, I experienced this first hand when I tried subjecting ChatGPT to TT. As long as one steers away from questions that led it to overeagerly admit its “programhood,” ChatGPT can be very convincing to have a mind. It is only after a while that it starts showing its programhood without explicitly stating it, by a lack of understanding a joke, a detachment from the current context in its replies, and so on. So, the process of providing an answer to the yes/no TT question does end under certain inputs, that input being ChatGPT itself.

What about our hypothetical hyperrealistic humanoids outside, roaming about the place? We might be tempted to halt on the answer “yes” to our yes/no TT question based on our comfort in ascribing them minds, but the ChatGPT example here should cast a shadow of doubt on that answer: What if they haven’t failed the test yet, but will fail in the future? This is especially easy to conceive when we know the limits of a program such as ChatGPT, which is exclusively text-/language-based, and so fails in other aspects such as computing the product of large integers. We can easily admit that it doesn’t have a mind when it seemed to previously since it reached the end of its programmed capabilities. But how about when we don’t know whether the agent is “programmed” or not? What to make of it then?

The point of the above discussion is that an agent cannot be said to have passed the Turing Test, only that it has not failed it – yet. This is of the same spirit as attempting to go about the halting problem by hardcoding a “does not halt” output as long as the program in question is running, and switching to “halts” the moment it halts: Although we have an answer, we can never be sure that it is the right one.

In light of this observation, which remained untethered from the content of the course so far, I would like to go back and propose a dissolution to this problem I have laid out. I have been discussing the passing or failing of the Turing Test deliberately as a dichotomous problem, and with good reason. But what if this is not necessarily the case? What if, as Newell says, the passage or failure in TT is a false dichotomy in mind possession?

This proposition, I believe, adds up quite nicely with Simon’s bounded rationality. If we admit that humans as the most evident mind-possessors have bounds to their minds, we also inadvertently admit that there are some more capabilities that can also be performed by a mind – it is just not within the reach of our minds. Let’s call such a mind a Mind++, a mind that performs everything a human mind can, but also more. What would an intelligent being with Mind++ think of us? If it had a corresponding Turing++ Test that relies on what our minds cannot do but a Mind++ can, then it would conclude that we do not have minds! We have two options: First, we give up and say that we do not possess minds. Second, we admit that having a mind comes in degrees. Mind possession can only then be relieved of its dichotomous conception, and the question becomes not whether something does or does not have a mind, but to what degree it has a mind. The agent can have less of a mind or more of a mind.2 To this, I can further add the only fact we know about the mind, one that we reiterated many times during the course: The fact that it evolved. This evolution of the mind can then be seen as the long and tedious process of going from no mind to some mind, and then eventually to our mind.